by Maureen Cooper | May 29, 2018 | Compassion, Kindness, Relationships, Yourself

In the UK three out of 4 people have been so stressed at least once over the last year that they have felt overwhelmed, or unable to cope.

This statistic is from a recent report for the Mental Health Foundation which shows astonishingly high levels of stress. Isabella Goldie, director of the Foundation is quotedas saying, Millions of us around the UK are experiencing high levels of stress and it is damaging our health. Stress is one of the great public health challenges of our time but it is not being taken as seriously as physical concerns.

With Mental Health Awareness Week focusing this year on stress, there has been quite a bit of media attention around stress-related issues. As someone who has been going through a bit of an intense time recently, it got me thinking about how meditation helps with working with stress.

Seeing the problem

During a particularly hectic day a couple of weeks back, a friend messaged me wanting to talk through a problem she was having with someone in her family. I did my best to be there for her. I listened, I responded but slowly it crept up on me that I was having to try really hard to have an open heart because none of it seemed as challenging as my own bad time. I was almost resentful that she kept going on about it all! That was a bit of a shock. It brought home to me that somehow what I was dealing with was intense enough to affect my open heart. I needed to re-apply my attention to how I was applying my meditation practice in action.

Here are some of the ways I have been trying to work with managing bad times in a way that enables me to maintain an open heart—a heart that is open and available to what is going on for others, rather than being focused primarily on what is going on for me.

1. Respecting people’s wish for happiness while understanding suffering

It’s natural when you feel down to want to feel better. You just want to be happy and to get on with life. The key thing to remember is that is exactly how everyone else feels as well. Just about everyone we meet wants to be happyand not to experience suffering and pain. We would like things to go well for us and for us not to have to face disappointment, loss, and grief. We work hard to try and avoid having to face things we don’t like and don’t want.

Life shows us clearly that while there is nothing wrong with the wish to be happy it is not as easy as we might hope. No amount of money, possessions or fabulous holidays will protect us from the challenges that life can bring. Every day each one of us is getting older, sometimes we get sick and one day, eventually, we will die.

The truth is that suffering is part of life. We won’t manage to live a care-free life! Nothing is permanent, everything is constantly changing. Our lives are made up of a string of moments that we weave together to try to make a whole, when in fact, we have no idea what each minute will bring. Just because we wake up each morning and go through our usual routine does not mean that the routine is cast in stone. Consider people having to flee their homes to escape, fires, or flooding or volcanic eruptions.

None of this means that we should not seek happiness but perhaps we can open our hearts to include everyone’s wish for happiness, not just our own. Perhaps also we can ease the intensity with which we long for happiness by accepting the inevitability of suffering. When we can acknowledge that things are tough, we give ourselves a chance to learn about what we are going through and how we could do things differently.

2. We are all in the same boat

All of this points to the fact that there is more that unites us as human beings than divides us. We might look different, with our own interests and dreams but joining us is a deep thread of common humanity. We all face worries about how we look, being in work, having enough money, finding love, caring for our families and staying healthy. In addition, we have strong imaginations and the ability to create worries simply from within in our minds. Anyone who has laid awake worrying at 04.00 in the morning will know what I mean.

As we have seen, we all look for ways to escape from our worries but it does not always work. As human beings we have to live with our imperfections, with our bodies that can seem so fragile and easily damaged and the impossibility of knowing all that we think we need to know.

Next time you are on a train, or tram, or plane try this exercise:

- Notice who your neighbours are—take a few moments to scan the compartment, tram or bus and to see as many of the other passengers as you can.

- Take note of the thoughts and emotions that pass through your mind as you do this:

—notice if you make a comment in your mind about someone

—notice the people you feel drawn towards and the ones you do not like the look of

- Try to imagine how they might see you as you sit, or stand alongside them

- Take a moment to be aware that everyone travelling with you wants their day to go well and to avoid any unpleasantness

—just as you do

- Then realize that inevitably for some people things will go wrong during the day

—let that feeling touch you and help you to feel a common humanity with your fellow travellers.

Doing exercises like this helps to remind us of how things are for other people. We are reminded of the deep thread of inter-connectionthat runs through all of human experience, and we are reminded that it is not just us who struggles. Realizing that just as we can be in pain, so can others can help to keep an open heart.

3. Helping others helps you

When we feel down, it can be hard to find the energy to do something for someone else but if we can make the effort, the benefits are considerable.

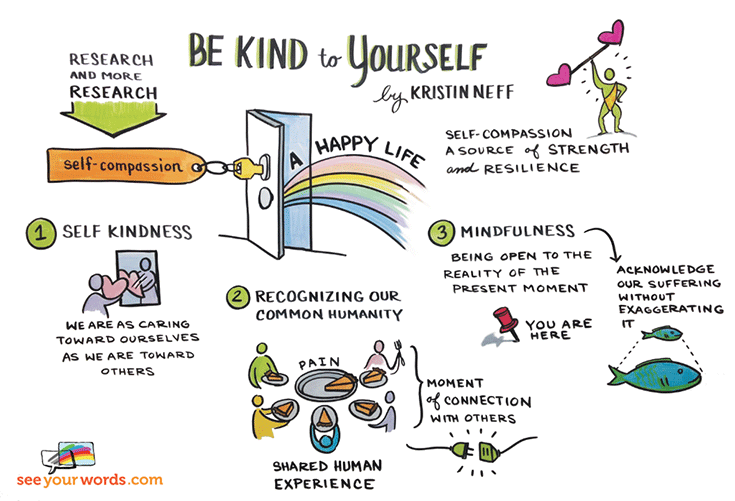

Research shows that kindness can improve heart function, lower blood pressure, slow aging and strengthen our immune systems. The author and scientist, David R. Hamiltonexplains that through the production of the hormone, oxytocin and the neurotransmitter, serotonin our levels of wellbeing are raised. Anxiety, stress and depression can all be reduced through preforming genuine acts of kindness. In his ground-breaking book, The Healing Power of Doing Good, Allan Luks documented the good feeling that you get from helping others and which is now referred to as the Helpers’ High.Older volunteers suffering from arthritis and other painful chronic conditions found that their symptoms decreased when they were actively helping others.

The thing is that when we can pay attention to the needs of other people, it lifts our attention to the bigger picture beyond our own individual bad time. Stress and worry tend to close us down, whereas thinking of others widens our view and ensures an open heart.

4. Build your resilience

For me the foundation of all of this is my meditation practice. I was drawn to meditation in the first place because I wanted to understand how my mind works. I can’t say that because I meditate I no longer worry about what might happen in the future or go over things that have already happened because I still do. The thing is that I take it all much less seriously than before. I have come to understand that there is a quiet, spacious aspect of my mind that worry covers over, and meditation enables me to access. On one level this can simply be being present to what is happening for me right now—recognising that all I can be sure of is the moment I am currently living. On a deeper level, it is an acceptance of my thoughts and emotions because I know that they do not have to define me—that my mind is bigger than they are. So even when I am facing challenges and bad times, a part of me trusts that I have sufficient resilience to bounce back from it in time.

The neuroscientist, Richard Davidson places resilienceas one of the four skills of wellbeing. When we are so stressed that we say or do something we regret later, or when we are so overwhelmed that we feel threatened by everything we need to cope with, we are experiencing an amygdala hijack. The amygdala is the brain’s radar for danger and the trigger for the flight-or-flight response. During a hijack it over-rides the brain’s executive centres in the pre-frontal cortex. Davidson’s research into the effects of meditation on the brain shows that meditation helps to strengthen the pre-frontal cortex and weaken the right-frontal cortex, which registers depression and anxiety.We now know from neuroplasticitythat the brain can change according to experience and research is confirming that we can learn to increase our resilience to hard times through a regular meditation practice.

What can we take from this?

Having an open heart is not something we achieve and then take for granted. Keeping our heart open is a process and sometimes it is going to be hard. Maybe we won’t always feel we can make the effort but if we want to manage our bad times with kindness, and wisdom then we don’t really have a choice. Our own wellbeing is dependent on maintaining an open heart because within that openness lies many of the solutions we need to work through our bad times.

Hello there!

If you enjoyed this post and want to go further try this online course

HOW TO BE A GOOD FRIEND TO YOURSELF

You can find out more here

by Maureen Cooper | May 3, 2018 | Kindness, Relationships, Stress, Work

When you are getting ready for work in the morning, is there a work colleague who comes into your mind who you dread seeing, and would rather avoid? If there is, then the chances are that you have a difficult person to deal with at work. Unfortunately, it’s not likely to be a problem that only you are facing. Difficult people at work can cause a ripple effect that has negative consequences throughout the workplace.

Everyone is difficult some of the time of course, so what does it take to be seen as a ‘difficult person’? There are people who complain all the time and are impossible to please. Then there are others who seem to want to turn everything into a competition, or worse, a battle. I have worked with people who treat their staff pool as a free audience for them to play out their own personal soap opera—they demand attention and tend to suck all the energy out of a team. Perhaps you’ve met the perfectionist? Someone who cannot accept anything that is less than perfect and projects their exacting and unrealistic standards on everyone around them. Quieter but just as deadly is the person who quietly goes behind everyone’s backs and gossips and manipulates to get their own way.

Toxic behaviour of any kind takes up time, energy and resources to deal with—all of which could be applied to the actual work to be done. Such behaviour can impact productivity and lower inspiration and morale among any team. It causes stress, absenteeism, and a higher rate of staff turnover.

However, it does not have to be all bad. Difficult work colleagues can help to focus our attention and encourage us to check our own habits at work. Let’s look at some practical, accessible steps that anyone can take to help them to deal with a difficult person at work without risking any of these negative outcomes.

-

Paying attention

Maybe as you read this you are thinking that you are always paying attention, and this is too obvious to mention? Perhaps you have not heard about the researchthat was done at Harvard University in 2010. It showed that for almost 50% of our waking hours, we are thinking about something different to what we are doing. This means that for almost half our life we are not fully present to ourselves and what we are doing.

Let’s take a moment to consider what that means. If our minds are elsewhere when we are interacting with another person then we are going to miss all kinds of signs as to what is actually going on. Our memoryof the interaction will be flawed and incomplete. We are going to be seeing people and events as we think they are, rather than how they actually are.

This is particularly important when dealing with a person we experience as difficult. We are going to need to able to discern clearly the other person’s behaviour, as well as our own responses to it. It won’t help to get caught out by defensive reactionswhich could add to the problem. Things will only get worse if we exaggerate the difficult behaviour of the other person. Developing equanimity, on the other hand will give us the grounding we need to understand and work with the challenges they present for us.

What we can do

One of the best ways to learn to be present is to make mindfulnesspractice part of your everyday life. Try to spend at least 10 minutes every morning sitting on a cushion, or hard-backed chair connecting with your breath. Simply rest your attention on the rhythm of your breathing. When your attention wanders away, notice it has wandered and bring it back. Keep doing this over and over again. Slowly, steadily you are training your mind to be present.

During the day we can use STOP moments—very short moments of mindfulness meditation.

This is how they work:

- Pause with whatever you are doing

- Connect with your body, feel its strength, let it ground you

- Take a few deep, slow breaths—release any tension you are feeling

- Let your thoughts come and go without chasing after them

- Enjoy the few moments of calm and spaciousness.

- Take that feeling with you as you pick up your activities.

-

Listening well

I don’t think I have ever met someone who owned up to being a poor listener. Each of us believes that when people talk to us we hear what they are saying. Sadly, most of the time we only just scratch the surface. We are used to putting our case, telling our story and we want others to listen to us. If we put ourselves in the centre, then it is hard to embrace the whole circle. Much of our listeningcomes from a place of believing we have the correct response, or the right solution and we can’t wait to share it with the person we are talking with. That comes across for the person talking to us, who senses that we are putting our own reactions ahead of their needs.

Susan Gillis Chapman has written a book, The Five Keys to Mindful Communication in which she uses the three colours of traffic lightsto help understand the different levels of communication. When we have someone at work who we are having problems with, the chances are that our communication is going to be the red light, where defensive reactions are predominant. At these times, how we listen is of over-riding importance. Our difficult person is expecting to not be heard, is almost provoking misunderstanding. We cannot afford to shut down and close ourselves off from the signals they are sending. If we can demonstrate that we are trying our best really be present and to listen without the inner commentary of our own opinions, then we have a chance to move to yellow light communication, where things can become more fluid. Of course, our goal is the open communication of the green traffic light.

What we can do

- Try to avoid conversations with your difficult person when you are tired, hungry or stressed.

- When you know you are going into an interaction with them, try to take a STOP moment beforehand.

- Listen with your heart as well as your head.

- Ask yourself what is really going on for the other person.

- Look for any emotional clues.

- Watch out for repeated words or phrases—the chances are these are the issues that are on the other person’s mind the most.

- Consider your attempts to listen with an open mind and heart as your contribution to healing the situation.

-

Give up judging others

Jon Kabat-Zinn, one of the leading figures in the mindfulness movement, described mindfulness as being, an intentional, non-judgmental awareness of the present moment. Why was it necessary to highlight this quality of non-judgment? If you think about it, we judge just about anything. In fact, we divide the world up into things we like and want, things we don’t like and don’t want and things we don’t really care about. We spend a great deal of effort going after the things we want, because we think they will make us happy and avoiding the things we don’t want, because we know they will make us unhappy. The thing is that none of it works. Lasting happiness is much harder to achieve than we thought and it’s hard to avoid challenging things happening to us.

Our like, don’t like and don’t care attitudes are just as easily applied to people we know, as it is to the things that happen to us. We hold our friends close and avoid people we do not like and in between is a huge mass of people we don’t ever really pay attention to. If we have a difficult person at work, they are likely to fall into the category of ‘don’t like and don’t want.’ Obviously, this is a weak position to try to find a solution from.

What we can do

We already mentioned the importance of equanimity as a basis for working with difficult people. It enables us to be present to the person and the situation but to not be drawn into it, to not be affected by it.

- Without equanimity we are defenceless in the emotional territory of the difficult person.

- With equanimity our limbic systemis under control and our neocortexis in charge.

- We can see things as they are, rather than from the point of view of our own self-focus.

- It is not necessary to draw courage from judgments which enforce our own opinions and prejudices.

- Equanimity allows us to be open to what happens, rather than pre-judging any outcomes.

-

Try kindness

It is easy to think that we don’t have time for kindnessin the workplace but this is a misperception. Being kind does not take more time, it just requires us to be present to ourselves, our work colleagues and the situations we find ourselves in.

Jonathan Haidthas researched something he calls elevation, or a heightened sense of wellbeing. This is the effect of people either experiencing kindness themselves, or witnessing it happening between other people and feeling the benefit personally. When this kind of interaction happens in a work environment it has the effect of building trust, commitment and loyalty. How we try to deal with a difficult person at work can contribute to the overall wellbeing of a workplace.

We’ve seen that it is all too easy to want to avoid difficult people at work, and to not have to deal with them—but let’s take a moment to try and see this from their point of view? Few people set out to be disliked—if their behaviour is provoking dislike, somewhere that is probably causing them distress.

What we can do

- Ask yourself what you know about your difficult work colleague

—are they under stress, is there something going on at home?

- Look for any small thing that you like about the person

—maybe you have the same taste in music, or they like the same movies that you do?

- Try to separate the person from their actions

—all of us do stuff which is not always nice, but it does not mean we are all bad people.

- Whenever you can, try to give your difficult person the benefit of the doubt.

- Observe how they are with other people

—are there other people they get on well with?

—I once had to work closely with someone who said I reminded him of his mother (with whom he had a problematic relationship). Although I found working with him very intense, I noticed that many other people sought him out for collaboration. The problem was something sparked very directly between the two of us.

-

Don’t forget yourself

Having a difficult relationship at work can be very disheartening. We can feel guilty, inadequate, somehow reduced by being embroiled in a difficult communication. It’s important to remember that we are one part of the puzzle and that the problem has many elements. At the same time, it helps to recognize that although we might not have started the problem it is inevitable that somewhere along the line, we could play a role in perpetuating it. We need to take time to look into our own behaviour and check our own emotional habits and vulnerabilities.

My main meditation teacher always used to say that if you want to remove a difficult person from the world, you can begin by looking into where you need to disarm your own destructive tendencies.

What we can do

- Show yourself some kindnessand understanding when you are under pressure

- Take steps to manage your stress and enhance your wellbeing at work

- Try not to take things personally

- Make mindfulness meditation part of your daily routine to help refine your discernment, develop equanimity and keep things in proportion.

Hello there!

If you found this post helpful and would like to go further, try this online course

9 WAYS TO COPE BETTER WITH YOUR WORK FRUSTRATION

You can sign up here https://www.awarenessinaction.org/cope-better-with-work-frustration/

by Maureen Cooper | Feb 26, 2018 | Meditation, Scientific research, Yourself

Emotional by nature

If you are interested in astrology, then you will know that for those of us born under the sign of the crab, much of our interaction with the world is carried out through the currency of emotions. Even if you are not interested, as a Cancerian, I can tell you it is true. As a child I remember being overwhelmed by the range and power of my emotions. One minute I could be blissed out with happiness and then minutes later, plunged into a vortex of sadness. I was my parents’ first child and they were not at sure what to do with the emotional rollercoaster I seemed to live on.

An early memory

I have a painful memory of being in school and something—I don’t remember what—going badly wrong in the classroom, and me ending up in the cloakrooms, locked in a cubicle and howling with rage and anguish. I was in those early stages of puberty, when everything is already heightened to an almost unbearable degree. A teacher came to find me and to insist I get control of myself—she didn’t offer any advice as to how to do that. The school rang my mother and when I got home, I got a major lecture of the importance of growing up, being responsible—and yes, learning to control my emotions.

The thing is that until I came across meditation, I never found anyone who could give me meaningful advice on how my emotions worked, why I was more emotional than my sisters (a Gemini and a Taurean), and how to deal with them beyond learning to control them—which I came to understand, meant supress them. When the emotions were positive, things were intense but manageable but when negative emotions got the upper hand, I felt helpless and totally at their mercy.

Neuroscience and emotion

With the developments in neuroscience, we can understand more about the relationship between the brain and our emotions. Richard Davidson, a leading neuroscientist and pioneer in research into the effects of meditation on the brain, has developed his own system of six emotional styles. He claims that it is these emotional styles, rather than our passing emotional reactions, that shape the way we interact with the world. Furthermore, by understanding our personal emotional style, we can learn where we are the most vulnerable in terms of how we respond, and gradually earn to try new approaches.

Meditation and emotions

Meditation is a sustainable way of doing just that. When we work with our emotional responses in meditation we can come to see that there is nothing problematic with the emotion itself—in fact, it is just energy and a natural part of life. When an emotion is triggered it rises, lasts for a few seconds and fades away. It is our on-going stories—our prejudices, our habits, our longings that cause us to go back and rekindle the emotion and replay it over and over again. We want to hold our ground, and to make things real and solid, so we use our emotions to back us up. Meditation helps us to view this parade of reactions without hope and fear—just to acknowledge what is happening and then let it go.

This is important because when we are in the grip of strong emotions we might think we are establishing a position, but it is built on an insecure foundation. In 2005 Dalai Lama attended a conference in Gotenborg, where he met Dr. Aaron Beck, the founder of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT). During their conversation they struck up a great rapport and shared insights that showed similarities between Beck’s work and Buddhism. The Dalai Lama was particularly struck by Beck’s assertion that according to CBT, when a person is angry 90% of their reaction is an exaggeration and a projection. People talk about ‘seeing red’ when they are angry. Perhaps this is a colloquial way of realising the truth of this research.

A story of emotions

I had an experience when I was out and about in Amsterdam recently that reminded me of this. After a long bout of ‘flu, my partner and I were enjoying a trip into town for dinner and a movie. He went ahead to collect the cinema tickets and I made my way to the restaurant. As someone who has rheumatoid arthritis, when I get tired my walking can get a bit unsteady. I came to a road junction and checked that it was all clear and began to step out into the road, when along the cycle track sped a young man on a scooter, with his girlfriend riding on the back. He saw me at the edge of the pavement and deliberating aimed his scooter towards me, making me wobble uncomfortably. He was delighted with my reaction and made a sort of ‘Ohhhh, ohhhh, ohhh!’ noise which he felt summed up my response.

He sped off laughing loudly, while I teetered on the edge of the pavement feeling a mixture of embarrassment, resentment and shame. For a few moments I could only stand there but then I glanced up and just caught a glimpse of the girlfriend looking back at me. Her expression was concerned and a little embarrassed as well. It helped to bring me back. Instead of feeling abused, and sorry for myself, my attention went to the guy driving the scooter. It was a Saturday afternoon, he had a girl to impress and a chance to show his skill with the bike—after all, he never came near to hitting me.

A quote from Taking the Leap by Pema Chodron

……when the whole thing is just not working and we don’t know what to do, this is the time when the natural warmth of tenderness, the warmth of empathy and kindness, are just waiting to be uncovered, just waiting to be embraced.

The whole incident brought to mind this quote from Pema Chodron. I had been on the verge of giving into a rush of emotion, which would have not shown me anything at all and certainly would not have helped the situation. The expression on the girl’s face acted as a reminder of how emotions work, which enabled me to turn the moment into a feeling of tenderness to the boy, trying so hard to be cool. The incident has come to mind several times since it happened. The line between realizing what is going on with an emotion and being swept away by it can be very thin. Fortunately, in this situation my own vulnerability acted as a support for seeing vulnerability in the one who was triggering my emotion and I could drop the rest of the story.

Hello there!

If you find this post helpful and would like to know more about meditation, you could try this online course

by Maureen Cooper | Nov 23, 2017 | Kindness, Meditation, Mindfulness, Work

The Changing Face of Work

At the height of his career my father occupied a senior position in a local government architectural department. He had a large team that he was responsible for and had to conduct delicate negotiations with councillors and politicians. In spite of his heavy workload my memories are of him coming home for an early dinner every evening. We had uninterrupted weekends and the regular round of holidays during which—because this was pre-technology—he was never pulled away by emails, texts, or reports to finish on his laptop. His work life balance was never in question.

Few of us would recognize such a working environment nowadays. For most of us technology has helped to break down the barriers between work and home. We can work on stuff from home and look for friends and partners at work. We don’t expect to keep one job for life—moving along a predictable career path does not feature as a realistic goal in today’s more fragile economy. Perhaps most important of all, we long for a sense of meaning and purpose at work—a feeling that with our work we can make a real contribution. Daniel Pink in his book, Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us reveals that the idea that we work primarily for money is a fallacy. Of course, most of us need to earn a living but we are also motivated by the need to direct our own lives, to learn and create new things and to do better for ourselves and for the world. Belinda Parmar in her book, The Empathy Era backs this up with this statement,

69% of Millennials said they would work for less money at a company whose culture and values they admired.

Challenges to finding a good work life balance

However, this goal is not one that is always fulfilled for people. In his book, How to find fulfilling work, Roman Krnaric writes,

Most surveys in the West reveal that at least half the workforce are unhappy in their jobs. One cross-European study showed that 60% of workers would choose a different career if they could start again.

An article in the Irish Examiner last autumn stated that 82% of Irish workers are experiencing stress at work.

The thing is that the brain interprets the workplace primarily as a social system. This means that it responds to work events with corresponding threat and reward dynamics—a clash with your boss will feel as important to the brain as the need to find food and water. Social pain is processed in the brain in the same way as physical pain, so threats to our status, security and wellbeing at work trigger the same circuits in the brain as threats to our physical safety.

A carrot and stick work environment will enhance this threat response leading to high levels of stress, whereas being treated fairly, feeling that work is meaningful and that one’s contribution is valued will help reduce stress and lead to a more harmonious, productive work environment. A stressful working environment will close down creative possibilities in the mind and have corresponding effects on output.

What are the qualities of a workplace that values wellness?

A work environment that provides good standards of wellbeing is more likely to be made up of people who are more loyal, more productive and provide better customer satisfaction. It is an outdated view that holds that staff wellbeing is an optional extra.

A recent report published by the New Economics Forum, identified five elements that are fundamental to wellness in the workplace.

-

A healthy work life balance

People want to work hard but not excessively so. Those working more than 35-55 hours a week tend to experience higher levels of stress.

-

Staff feel their skills are used and acknowledged

People want to contribute according to their level of expertize and to feel they are developing in their jobs. Feeling under-used is a potential source of stress.

-

People experience some degree of control in their jobs

Few people welcome being micro-managed and want to establish relationships of trust with their managers in order to enjoy a degree of autonomy at work. When this is not present, then stress levels rise.

-

Healthy work relationships

Workers want to have relationships at work that are supportive, respectful and understand mistakes, while avoiding blame. The impact of positive working relationships can be more influential in job satisfaction that an increase in pay.

-

Fair pay

After a certain level of remuneration, the benefits to wellbeing decrease but if income falls below a basic level then levels of job satisfaction decrease accordingly.

When these factors are in place, the workplace is more productive, efficient and happy place to work. Employees are less stressed and more satisfied with their jobs. They experience more loyalty and engagement and staff turnover is lower.

How meditation and compassion help in establishing good work life balance

Research conducted at Harvard University in 2010 found that for 46.9% of our waking lives we are thinking about something different from what we are doing and that this mind wandering does not make us happy. This means that for more than half of our time at work we are operating on a kind of automatic pilot and we are not fully present to our own experience or to the people around us. Meditation has been practiced in the Buddhist tradition for more than two thousand years but within the last twenty years research from neuroscientists is providing a foundation for what practitioners of meditation already know—it helps us to develop our attention and to become more present.

When we are able to stay present rather than ruminating on what might or might not happen if we take this or that action, we free up a lot of our energy and attention that would otherwise be caught up in anxiety and stress. We have the capacity to listen to other people without running a commentary in our minds that overshadows what they are wanting to communicate to us. We can manage our own emotions and moods more effectively because we can see more clearly what we are doing. From there it is a natural development to manage relationships with others with more openness and tolerance and less criticism and judgement.

Psychology professor, Jonathan Haidt has coined the term ‘elevation’ to describe the ripple effects of acts of kindness. We do not need to be involved in the action ourselves but simply by witnessing a person perform a kindness for another we experience an uplifting feeling, which makes us feel good. Applied to the workplace actively developing kindness and compassion helps to spread an attitude of service and commitment among staff. As they learn to care for themselves with compassion they extend that heightened understanding to others.

As with meditation, a compassionate working environment is likely to encourage staff to stay in their post, to need less sick leave and experience a reduction in stress.

What can we do as individual employees?

The great news is that meditation and compassion are trainable skills. We can learn to work with our thoughts and emotions in order to achieve a higher degree of wellness at work. The big take-home message from neuroscience our that our brains change according to our experience. As we start to train ourselves in meditation and compassion our brains gradually change to support our new habits.

As we saw earlier, having a sense of being in control at work is a very important factor in wellness and yet for so many of us this seems out of our reach. So much of what we do at work is in response to directives we don’t always agree with, for people with whom we feel we have little in common. The answer here is to learn to take control of ourselves in a fresh and meaningful way. We can pay attention to how we draw on our own strengths, skills and experience. Through training in meditation and compassion we can take control of how we react to any situation—whether it is one we like, or one we have trouble with. We can learn to view our work colleagues in a new light and try giving them the benefit of the doubt rather than feeling frustrated and stressed.

At the heart of it all is learning to view ourselves with kindness and compassion. Instead of demanding an unreachable level of perfection from ourselves we can learn to work with our imperfections and vulnerabilities with mindfulness and kindness. This gives us a stable foundation from which to reach out to other people in the same way.

Hello there!

If you found this blog useful, you could try this online course

9 Ways to Work Better with your Work Frustration

You can find out more here

by Maureen Cooper | Nov 14, 2017 | Kindness, Mindfulness, Work

Very few of us are likely to set out for work with the intention of upsetting people. Mostly we want to do our job well, and get on with our day. How is then that so often we come home in the evening feeling annoyed by an interaction we have had and upset with a colleague? It got me thinking about whether anyone went home in the evening with bad feelings towards me!

Here’s some thoughts I had about ways in which it is possible that I might have got it wrong—without meaning to—and upset people at work.

-

Being too pre-occupied to listen well

Do you get impatient while people are talking to you? Are you tempted to jump in and make their point for them—because you see it already and more clearly than they seem to? Do you have to hold yourself back from interrupting?

The thing that I have come to notice is that people feel your impatience and it makes them uneasy. They don’t take it as a statement on your state of mind but on their performance and it makes them feel that they don’t have your full attention—which makes them less able to get their message across and increases your impatience.

These days I try to see listening as part of my meditation practice—part of being present, awake and curious. You miss so much by thinking you already know what someone wants to say, or by responding too quickly and cutting them off.

When we can allow someone the space to say what they want to say we are creating trust and communicating respect—so we are fostering harmonious relationships. We are creating opportunities to exchange useful information and to explore problems, which will help to boost creativity in our team.

-

Taking people for granted

It’s only human to want to feel appreciated at work. A recent survey found that 66% of employees said they would quit their jobs if they felt unappreciated. This figure jumped to 76% among millennials.

It’s all too easy, when you are busy, to push ahead in order to get the job done and to overlook how people feel they are being treated. Of course, this is intensified if you are in any kind of managerial role, with people reporting to you.

In his book. 365 Thanks Yous, John Kralik tells the story of how he turned his life around by writing a thank you note to a different person every day for a year. Finding himself at a critical point in his life, he wanted to try and focus on what was good in his life, rather than what was going wrong. One of the stories that always sticks in my mind is the day he wrote a thank you note to his server in his local Starbucks. At first the guy thought he was being handed a letter of complaint and then he was amazed at being so beautifully thanked for something he did over and over again all-day long.

A lot of my work is carried out at a distance—through SKYPE, email, and online courses. Yet I find the power of appreciation is not diminished by distance. It shows you have noticed the effort someone has made, and you are the better for it. You need to do it because it feels right, if you are hoping for something in return it can get messy.

-

Talking about people behind their back

It can be seductive and oddly flattering to be pulled into a session of bad-mouthing your boss, or a fellow worker. For a while you can feel that you are accepted, and one of the in-crowd. You are being trusted to hear and share in the discontent someone is feeling. We all do it from time to time but when it happens as a routine part of each working day it can become unhealthy and potentially hurtful.

This was brought home to me very strongly during the years that I worked as part of the Executive Board of an international non-profit. I was the only woman on the team of four and many of our staff and volunteers in the national teams were women. Unfortunately, for some people I was an object of some envy and resentment. I was too slow to understand this and took too long to take measures to address it. After some time in the job—which I loved—I was told about stories that were circulating about me. Most of them were just inaccurate and came from people’s projections. Others had some truth but were recounted without a shred of empathy or understanding of the challenges that I faced.

I was shocked and devastated for a time but when I calmed down, I saw this was a great learning opportunity for me. There is nothing like being on the receiving end of gossip and speculation to help rid you of any inclination to engage it in yourself. I would never want someone to feel as I did during that period.

When you gossip about someone behind their back you erode trust. It always seeps out somehow and people come to know you’ve been talking about them. It’s difficult to ask them to trust you after that. Much better to approach someone directly to talk something through that is bothering you.

-

Not giving someone the benefit of the doubt

Imagine a situation where one of your children wakes up in the night with an upset stomach. You spend hours caring for them, changing sheets, bringing glasses of water and finally drop off to sleep at around 04.30. Your alarm goes off at 07.00. You have a splitting headache but you get out of bed because you are due to present a new project to your team at work at 10.00 that morning. Your child is over the worst but won’t be well enough for school. It takes almost an hour to arrange childcare and now you are late leaving the house. The train is packed and you don’t find a seat. By the time you get to work you are feeling very sorry for yourself but you do your best to give an inspiring presentation. It goes OK but lacks your usual flair and the team is doubtful and critical about the new project.

Your boss asks for a word after the meeting. He/she could take a number of approaches to your disappointing performance. He/she could start off by pointing out how flat you were and how your answers led to more, rather than less confusion. Or he/she could sit you down and ask what was going on and what help you needed to sort this out.

Which approach would you prefer?

When people behave in ways we are disappointed in, or uncomfortable with instead of immediately reacting, we could ask ourselves questions like these:

- what might be going on for this person that I am not aware of?

- what do I know about their situation which might help me to understand what is going on?

- what can I do to support them?

These questions open a dialogue, which could lead to a solution of the difficulty, rather than an angry exchange.

-

Forgetting to include people

If we feel excluded from an event, we might say that our feelings were hurt. Neuroscience is showing that this might be more accurate than we thought. Research shows that the same area of the brain—the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex—is active when we process emotional/social pain, as when we feel physical pain, say from catching our finger in a door.

Our ancestors evolved to live in groups because they understood that the resulting protection was essential for survival. A sense of wanting to belong is hardwired in us and when we don’t feel we are included, then our threat response is triggered and we can become anxious, and uncooperative. The activation of the stress response uses resources that would normally go to the pre-frontal cortex, the area of the brain we use for—among other things—problem-solving, and memory. When we are under stress, we are more likely to make inaccurate assumptions.

It’s this kind of reaction that can lead to someone trying to create their own sense of belonging. This is where potentially toxic behaviours such as gossiping, cynicism, and forming cliques can come in.

It makes good sense at every level to foster an environment of openness and inclusivity in your workplace. It helps to make sure information is easily accessible, and people feel encouraged to comment and feedback on work processes. Ensuring all views are heard in meetings, welcoming and supporting new and younger staff is important. Then there are the small everyday events that can have such a big impact on people. Things as ordinary as remembering to make coffee for all members of your team, including everyone in your morning greeting and spreading your invitation to lunch widely. All this helps to create a sense of inclusivity and belonging.

-

Being too anxious to trust a colleague

Few employees enjoy being micromanaged. It leads to people feeling not trusted, undervalued and over-controlled. It is also exhausting for the person trying to micromanage. If you are continuously looking over your shoulder to check on what each member of your team is doing, you never have enough time and energy to do your own work. It’s a self-defeating process. The more you micromanage someone, the further it saps their creativity, ending up with them increasingly dependent on you.

No-one wants to be an irritating manager. Micromanaging is often rooted in an anxiety about one’s own abilities, and an insecurity around your position. Perfectionism usually part of the mix—not having the confidence to let people have the space to experiment and even to fail. Instead you feel bound to monitor each step of the way, so you can check for anything unexpected along the way. You are afraid to fail yourself, and so you project it on to everyone working with you.

One way of lessening your own anxiety and allowing an employee to feel valued is to ease up you focus on doing. Micromanaging is worst around getting things done and achieving the right goals. Of course, we need to do that but not at the expense of being. If we are paying attention to how we are when we take on a task, rather than simply on getting the task done—then we might be open to starting a dialogue with the people we work with. We might consider asking them to give feedback on how we manage, or to share what they feel are their main skills. It can be possible to ask if, or where they feel blocked. Perhaps it would be possible to share some of your own concerns and to talk together about how to work together with more attention to the process of the work.

Opening up the one-way dynamic of micromanaging could hold surprisingly helpful answers for both mangers and staff.

Do you have any stories you would like to add? It is always good to hear from you.

Hello there

If you find this post helpful, you might like to try this online course:

9 Ways to Cope Better with your Work Frustration

You can find out more here